"Group Polarisation: An Online Menace"

Russia’s recent invasion of Ukraine was an event that shocked the world. Many people have banded together online in a united effort to condemn the actions of Vladimir Putin and to stop this war. As part of this movement, people have been calling for companies to stop doing business in Russia. For example, an article in the Washington Examiner documents that #BoycottCocaCola was trending on Twitter in response to Coca-Cola’s continued operations in Russia (Kerr, 2022). However, with the sanctions from the EU and their removal from SWIFT, the provider of international financial transactions, Russia’s economy is already under a lot of pressure. In my opinion, stopping these companies from operating in Russia would make more of an impact on the everyday lives of its citizens than on stopping the war. As such, I see the call for many companies to stop doing business with Russia as a case of online discourse becoming more and more extreme as time passes.

In social psychology, this would be classified as a case of group polarization, which is a phenomenon where the group members’ attitudes shift towards a more extreme point after interacting with each other. An example of this would be the experiment by Myers and Kaplan (1976), where participants were asked to be part of a mock jury. Participants first gave their judgments on eight cases before discussing half of those cases with the other subjects. After the discussions, they were found to be more extreme in their judgments, becoming more harsh when the case was highly incriminating and more lenient when the case was less incriminating.

In my opinion, group polarization was not much of an issue before, as groups of like-minded people could not often meet up due to the constraints of time and distance. However, in the era of social media, it is extremely easy to meet and interact with like-minded people. In addition to that, people do not even need to be online at the same time as discourse can still occur by just leaving a comment or tweeting at one’s own convenience, leading to group polarization.

For the reasons mentioned above, I think that social media is the perfect breeding ground for group polarization, and from my own experience this is a problem that has already manifested itself online. Take Twitter for example. The platform is filled with a countless number of groups that all have beef with each other due to being unable to find a middle ground because of the extreme stances that they all take. Some users have even begun to develop a mentality where you are either with us or against us, unable to see the world in anything other than black and white.

One might argue that because of how easy it is to access information on the internet, people would have many opportunities to interact with different political perspectives online than they do offline. In theory, this should prevent the formation of echo chambers, environments where people are only exposed to perspectives that agree with their own, and prevent group polarization from occurring. However, in a study by Hong and Kim (2016), they found that the Twitter accounts of politicians with extreme political ideologies had more followers than their more moderate peers, suggesting that polarization does occur online. This may be due to confirmation bias, where people tend to look for evidence to substantiate their own beliefs. As such, I believe that people intentionally avoid exposing themselves to a wide range of opinions, instead forming echo chambers around themselves.

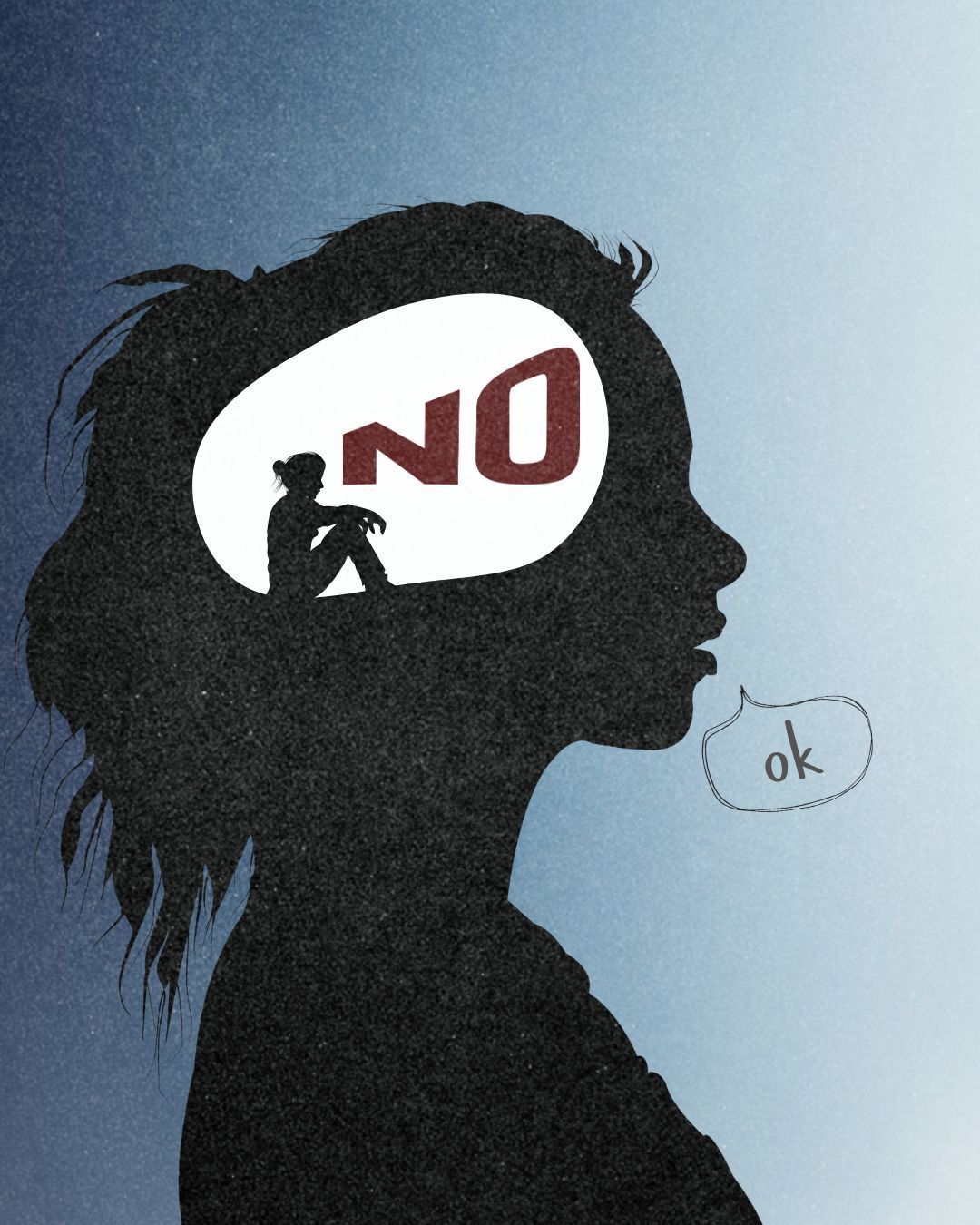

From what I have seen, group polarization has negative effects. There is the risk of groupthink, which traditionally means that there is a higher chance of a group making more extreme and risky decisions. In an online setting, I feel that group members do not interact for the purpose of making decisions, but rather to know what each other is thinking to get a feel of the general consensus. As such, groupthink still occurs via members of the group not raising any concerns about the current discourse, for fear of being perceived as going against the group. As a result of this, the perceived group consensus may not actually be representative of what each member thinks. An experiment by Guilbeault et al. (2021) has shown how easily it is for a consensus to affect what individuals think the correct opinion to have is, and I think that groupthink affects individuals in a similar manner. As a consequence of this, I think that group members may share opinions online that they later regret (Neil, 2017).

In addition to this, I feel that individuals who fall prey to group polarization are more likely to argue online, negatively affecting their mental health. I think that because they hold more extreme positions, it will be more likely for them to find people who disagree with them, and a little disagreement is often enough for an online squabble to begin. In a survey by Tait (2016), 35.8% of respondents said that online arguments affected their mental health. In addition to that, 2.6% of respondents felt the urge to harm themselves after engaging in online arguments and 11% responded that online arguments made their pre-existing mental health conditions worse. This hints at the notion that group polarization can be detrimental to one’s mental health.

To avoid these consequences, how should group polarization be presented? An easy way to do so would be to avoid creating an echo chamber. Try exposing yourself to as many opinions as possible from a diverse range of credible people. Besides that, if a discussion is held, it may be good for people to take note of their standings before the discussion and for someone to play devil’s advocate during the discussion itself (Sockolov, 2017). I sincerely believe that any group that takes these steps will be at very little risk of polarization.

References

Guilbeault, D., Baronchelli, A., & Centola, D. (2021). Experimental evidence for scale-induced category convergence across populations. Nature Communications, 12(1), 1-7.

Hong, S., & Kim, S. H. (2016). Political polarization on twitter: Implications for the use of social media in digital governments. Government Information Quarterly, 33(4), 777-782.

Kerr, A. (2022, 5 March). Calls to boycott Coca-Cola grow after company refuses to pull out of Russia. Washington Examiner. https://www.washingtonexaminer.com/news/calls-to-boycott-coca-cola-grow-after-company-refuses-to-pull-out-of-russia

Myers, D. G., & Kaplan, M. F. (1976). Group-induced polarization in simulated juries. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 2(1), 63-66.

Neil, S. P. (2017, 6 December). More Than Half of Americans Have Social Media Regrets. Huffpost. https://www.huffpost.com/entry/more-than-half-of-america_b_7872514

Sockolov, E. (2017, 7 September). How Group Polarization is Tearing us Apart. One Mind Therapy. https://onemindtherapy.com/social-psychology/group-polarization/

Tait, A. (2016, 7 October). Is arguing online actually good for your mental health? The New Statesman. https://www.newstatesman.com/science-tech/2016/10/arguing-online-actually-good-your-mental-health